How To Write A Lyric If You Don’t Know Music

Posted: September 24, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting, Songwriting Tips | Tags: How To Write A Lyric If You Don't Know Music, Lyrics aren't poems, Metronome Online Leave a commentTo write a lyric successfully, the music framework it will sit on must be accounted for. Lyrics aren’t poems. Lyrics are restricted by elements poems aren’t, elements that are part of music. This post is intended to get you thinking properly and give a concrete tip or two you can use, by no means can we completely explore this topic here.

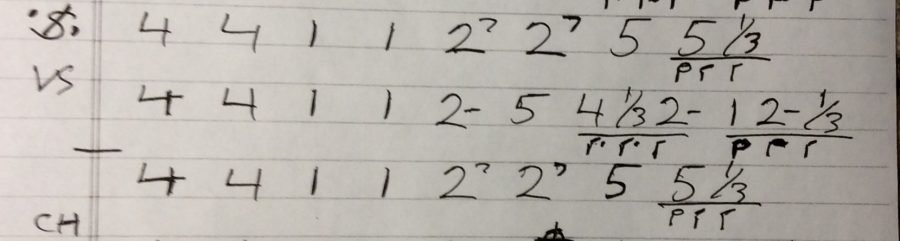

The biggest restriction on a lyric will be the measures (a.k.a. bars) each line has to exist in.

In 4/4 time there are 4 beats to a measure. The typical 4/4 song has 4 bars to a phrase, so 16 beats, and the beats are evenly measured. Let’s pull up:

Click at the top of the circle to fill the dot above “92” and it will begin to click at 92 beats per minute. That’s a medium tempo, not real fast, not real slow.

Count along each time it clicks. 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4.

Every 4 beats a new measure begins. In four bars of music those 16 beats are exactly how long your initial phrase should be. If each word gets 4 beats you could write four words total each receiving 4 beats: How about “I don’t know you.”

I don’t know you

1- 2- 3- 4, 1- 2- 3- 4, 1- 2- 3- 4, 1- 2- 3- 4

You are writing whole notes. Whole notes get 4 beats.

For the next phrase let’s use half notes, each word receiving only 2 beats except on the word “very” where we’ll give each syllable only 1 beat, so they are quarter notes:

and I do not like you very much

1 – 2 – 3 – 4, 1- 2- 3- 4, 1- 2- 3- 4, 1- 2- 3- 4

As you can see, unlike poetry where lines can be free form, music tends to impose restrictions that are mathematical in nature. Using an x to represent a measure, typically music in 4/4 looks something like this:

Introduction: x x x x

Verse 1: x x x x / x x x x

x x x x / x x x x

Chorus 1: X X X X / X X X X

Vere 2: x x x x / x x x x

x x x x / x x x x

Chorus 2: X X X X / X X X X

Bridge: x x x x / x x x x

Chorus 3: X X X X / X X X X

Chorus 4: X X X X / X X X X

If you chart out a basic diagram of the song format then start the click at the appropriate tempo you can write to it, ensuring the lyric will sit nicely in the music once it’s written- b.e. watson

Pre-Production : What Is It?

Posted: September 13, 2013 Filed under: Client News, Songwriting Tips | Tags: full band demo, limited release, nashville numbers Leave a comment I’ve set aside 1.5 hours this morning for pre-production on an original song titled “Into The Light” by songwriter Timothy Demming.

I’ve set aside 1.5 hours this morning for pre-production on an original song titled “Into The Light” by songwriter Timothy Demming.

Tim ordered “The Works” level demo ($1,250.00) which is a full band demo including lead, harmony and background vocals, a 6 piece band including doubling of tracks where warranted, mastering, and radio ready mix. It comes with a limited release license for up to 10,000 copies to be sold, either via download, CD or other means.

I loved Timothy’s rough and I’m excited to get started!

What happens in pre-production? This is the time production notes are made, the songwriter’s notes are reviewed, the arrangement is created and Nashville Number Charts are written. It’s also when the singer and musicians who will be on the session are chosen.

If I hear flaws in the song’s construction, be it in the lyric or in the music, I’ll shoot out e-mail(s) to the client noting the perceived problems and possible fixes. I realize that what I see as a problem may be something the writer did intentionally and wants to keep, which is perfectly okay.

Common problems resolved at this stage are:

- Extra bars that aren’t needed

- An odd number of bars that need to be evened out so that portion of the song doesn’t feel “left footed.”

- A line that is so wordy the singer won’t be able to squeeze it all in without sounding unnatural.

- A chord choice that doesn’t fit the progression or the melody.

- A melody that isn’t supported by the chords.

- Tempo slightly faster or slower than ideal.

- Weirdness. I can’t explain this exactly other than to say songwriters, left to their own devices without input or guidance, often do strange things, especially in the lyric. For example, they may write a complete song built on a concept that, unbeknownst to them, could also be taken another way they never thought of. Can you spell “sexual innuendo” and place it in parallel to a normal lyric in a sweet old ladies’ gospel song? Not the best idea to let that out in public, she needs some gentle guidance.

Or sometimes a song is just plain weird beginning to end: “What Does Santa Give Huskies for Christmas?” comes to mind. Perhaps there are some questions we just don’t need an answer to. Gentle. Guidance.

I don’t address things like pitch issues, tone or musical ability of the singer and players on the rough. If the songwriter making the rough version had perfect pitch, great tone, could play at session quality and do great arrangements what would they need us for? I expect those elements to be pretty raw, just send in the best rough you can muster. I’ll review your song, not how well you perform it.

Jesus will judge you someday, it’s not my gig : )- b.e.

Songwriter’s Market 2014

Posted: September 12, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting | Tags: Songwriter's Market, Songwriter's Market 2012, Songwriter's Market 2013, Songwriter's Market 2014, songwriting Leave a commentIs Songwriter’s Market 2014 showing the long tooth?

At one time Songwriter’s Market was a useful tool for pitching songs to publishers and record companies. But things have changed in the songwriting world. Times have changed.

Many songwriters complained about Songwriter’s Market 2012. According to most, it was badly in need of updating. One buyer revealed that most of her 2012 submissions came back unopened and undeliverable. Most comments on various retail sites are negative.

Songwriter’s Market 2013 had little updating from 2012 so if anything, it was even less useful.

What has changed since the early days of publication?

Songs are more in demand, not less. At one time there were three major TV networks, major motion pictures, PBS and radio. If your songs weren’t played in those places you weren’t making much money. Now there are far more outlets. Look at television alone: Hundreds of channels, most of which use music.

Internet websites, radio and Internet advertising use vast amounts of music already and use is increasing as the Internet changes from older users with large desktop systems who prefer reading words, to a younger demographic using smaller devices that prefers music and pictures. Music helps sell.

There are newer, universally accessible and arguably better ways to get exposure for an act than there were when Songwriter’s Market began publishing. YouTube, Facebook, etc. weren’t available fifteen years ago.

It’s possible the editors have become lazy in updating Songwriter’s Market listings. But regardless of the reason for the decline, it’s still a very useful book for researching music publishers and other music related companies. You can get names, e-mail addresses and more to help you start establishing contact.

But purely as a mechanism for marketing songs it has been coming up short for years now.

Does anyone care to comment on the usefulness of Songwriter’s Market 2014? -b.e.

Rewriting Your Lyric

Posted: August 13, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: free lyric review, Rewriting Your Lyric, songs floating in the air, Willie Nelson Leave a commentAmateurs write, professionals rewrite.

That’s an old saying but it’s mostly true. Great songs sometimes pour out in a fit of inspiration and need little or no tweaking afterward. Willie Nelson says he he sees songs floating in the air and just picks them out.

I don’t know, maybe I need glasses, I’ve never seen songs floating around for the taking but most songwriters do have a few works they claim wrote themselves.

In most cases though, that initial inspiration results in a rough draft that needs work. How do you know? If it’s not the best it can be, it needs a rewrite. Some songs are rewritten repeatedly over a period of years before they are deemed “there.”

Look for overused, tired phrases and replace them with something unique. Say the same thing but in a way no one has ever heard it put before.

If you used any “big words” to impress listeners with your brilliance, unless their use is necessary to the song and adds value, drop those words in favor of more common, conversational words. As with simple conversation you’ll impress a lot more people with fresh ideas and cleverness than with multiple syllable words that leave them thinking “He’s (or she’s) trying to sound smart,” instead of leaving them with no doubt you are.

Tighten up. Make your point in each line concisely, nothing wasted.

Don’t report, make people feel something. What feeling are you trying to evoke? Do you want the listener to feel something positive like empathy or love? Or something negative like anger? Is your lyric doing that? Make it happen.

Be open to outside input. I’ll be glad to do a free lyric review on any song you order a demo on, make suggestions and hold off scheduling it until it’s ready to go. Unless it’s a pretty extensive amount of input where I’m actually writing the lines or music instead of just making suggestions, I don’t ask for songwriting credit.

But too many times songwriters say they want constructive criticism then fight most of the suggestions that would bring the lyric up to the quality it needs to be to get a publisher interested- b.e.

Songwriting Chord Progression Tip: Root to Relative Minor

Posted: August 10, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: root chord to the relative minor, Songwriting Chord Progression Tip, voicing Leave a comment

Songwriters who aren’t trained in music theory often hear a song using a bass line movement descending from the major root chord to the relative minor, then imitate that movement in their own songs this way: (key of C) C, B minor, A minor. In the Nashville Numbers System that would be 1, 7-, 6-.

What they are actually trying to imitate is this: C, G/B, Am or in Nashville Numbers speak: 1, 5/7, 6-. The G/B means a G chord played with a B bass note. If you play guitar or piano and you’re solo you can make the movement happen by voicing the deepest pitched B note as your root for the G chord. But if you’re working with a bass player it’s fine to simply play the full G chord and let the bass player take the B bass note. Another example just to confirm you understand the concept, this time in the key of G : Instead of G, F#m, Em use G, D/F#, Em- b.e.

Songwriting Tip: It’s a Conversation!

Posted: August 8, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: a new rhyme choice, conversational lyrics, Forced rhyme, free rhyming dictionary, free rhyming dictionary online, Reversing the natural order of word, William Shakespeare Leave a commentWhen writing most lyrics it’s a good idea to keep them conversational. Ask yourself if the lines and words you write are the way you would say them if you were talking to a friend. Or at least the way someone would. Someone average, not a rocket scientist.

The problems that occur when you don’t do that are numerous. There are exceptions but forced rhyme, writing over people’s head, reversing the natural order of words, and misuse of adjectives by trying too hard to be descriptive, to the point of getting freaky, are bad things most of the time.

If you have a rhyming dictionary or even if you’re offered access to a free rhyming dictionary online I wouldn’t recommend using it much, if at all. In general, if a rhyme word doesn’t come to mind easily, looking for obscure ways to force the rhyme by using unusual rhyming words or phrases is usually a dead end. Forced rhyme (imperfect rhyme words that hopefully are close to truly rhyming) is okay and lots of hits have forced rhymes but force a rhyme too much and it sounds like it. It takes the listener out of the word spell you’ve been weaving successfully to that point as they ponder the oddness of the line.

Using a regular dictionary is fine. You may need to verify what a word means and that’s okay, but don’t start looking for synonyms so you can exchange two syllables for four. You won’t appear “smart” so much as you’ll lose listeners who won’t know what you’re talking about. You didn’t until you looked it up, why would they? For the most part, choose words you’d use in everyday conversation.

Probably the most common mistake I see is reversing the natural order of words. “To the park went we” may rhyme with “bee” but no one says it that way unless they’re trying to get their William Shakespeare on. The average person would say, “We went to the park.”

Reversing the natural order of words in a sentence usually hits the ear funny and breaks the spell instead of pulling listeners further into your story.

It’s weird. It’s not “unusual but in an artistic way” weird; man, it’s just plain weird. Write a different line. If you can’t find one you’ll need to fix the “bee” line first to give yourself a new rhyme choice.

And I guess that’s the bottom line for all these points: Does this word or phrase add to the song or detract? Does it pull the listener in further or momentarily push them out? The amateur considers neither, the pro considers both and lets the answers make the decision for them.

One exception that comes to mind because I’m working on it now is “Beautiful, the mess we are” in Better Than A Hallelujah. Obviously intentional and obviously awesome, it makes the song!

Anyway, for the most part, keep your lyric natural, conversational, and all will be well. Or maybe all well will be…hmmm, let me think about that, lol- b.e.

https://twitter.com/DaveWritesSongs/status/373685768616554496

Songwriting Tip : Adding A Suspended 4th in a progression

Posted: August 5, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting, Songwriting Tips | Tags: Adding A Suspended 4th in your song, chord, resolve, sus4, suspended Leave a commentIf you play the notes that comprise a D major chord: D, F# and A (the root, the third and fifth respectively) and raise the F# one half step to G, you have created a suspended fourth. It’s a pretty sounding chord and one you’ll surely want to use in at least a few of your songs. Note that all F#s voiced in the major chord would need to be raised to the G note.

The raised third note sounds like it wants to resolve back to the third so the easiest and most common way to employ it is by playing the suspended chord followed by the major (Dsus4 to D) or vice versa (D to Dsus4). You could do this movement once or several times.

So the formula is: root, 4th, 5th of the major scale. Example: To create an A suspended 4th use the A major scale as the basis which is A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, A octave. The root is A, the 4th note is D and the 5th is E so A, D, E are the notes of an Asus4.

There are other uses that will be covered in future posts.

https://twitter.com/JoshuanGonzales/status/372955420064641024

Songwriting Tip: Three Chord Groups

Posted: August 4, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: Bill Watson, Chord Chemistry Ted Greene, chord progressions, chord rules, chord substitution, guitar shop by bill watson, three chord groups, tonic dominant seventh Leave a commentKnowing a few chords on guitar or piano is a good thing but some roughs I’ve reviewed here reveal that some newbie songwriters aren’t sure how to use them together. Sometimes chords are used that don’t support the melody or several chords are used that inadvertently introduce a new key in a spot where that shouldn’t happen.

Hopefully this post will reduce that confusion slightly, but in the larger sense, it’s aimed at introducing the abecedarian songwriter to the concept that there is a right way and wrong way to use chords, thus fueling the desire for further exploration of the principles.

Huh, abecedarian… pretty good word, eh? It means neophyte or beginner. Use it to replace a cuss word: “Listen, you abecedarian…” : )

As in most endeavors, there are rules. Rules can be broken but songwriters who don’t know the rules in the first place tend to break them in a bad way, in a way that detracts rather than enhances.

So here is a rule of sorts: Inject a sense of order in the writing process by employing a chord progression, which is several chords played in sequence that sound good together and firmly establish a key. There are many chord progressions that are accepted in music theory as “standards” and are used over and over, the simplest being the three chord group.

Many hit songs are written using only a three chord group, some with as few as two of the three chords in a group.

The easiest three chord groups to play on guitar are:

1. E, A, B7th

2. G, C, D7th

3. A, D, E 7th

4. C, F, G7th

5. D, G, A 7th

All of those can be played on guitar using open chords (chords that contain unfretted notes). The first chord in the three chord sequence is the tonic chord a.k.a. root chord. The second is the dominant chord, the third is the sub dominant or sub dominant seventh.

A three chord group is based on the major scale. Choose the 1st, 4th and 5th notes of a major scale and those notes name the three chord group for that scale with that 1st (the root note) naming the key. Also add a dominant 7th (7th) to the final chord (although the 7th is sometimes omitted).

For example, the notes in a C Major scale are:

C, D, E, F, G, A, B, (and back to C, up one octave in pitch from the original C).

The 1st, 4th and 5th notes of the C Major Scale, counting from C are C, F, G. So in the key of C, (C because the first note, the root note, is C) the 3 chord group is C, F, G. In the Nashville number system they’d be referred to as 1-4-5.

Click here to read the rest of this post, including how to use a three chord group to write a song and how to employ the principal of chord substitution.

Or you can skip the free stuff and go straight to the books this post is drawn from, we’re barely scratching the surface here. If you want to learn very basic open chord progressions and simple rhythms get my book Guitar Shop. If you want to learn more complicated chords, extended chords, how non-root bass notes work and learn all the chord substitution rules, get Ted’s book– bill watson

Songwriting Basics: The Minor Three Chord Groups

Posted: July 29, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: 1-4-5, 1-4-7 chord, 2-5-1, i=iv-v, ii-v-1, Key of A minor three chord group, key of E minor three chord groups, minor three chord groups Leave a commentIn regards to the post on Three chord Groups, here are the most commonly used Minor Key Three Chord Groups:

1-4-5 (each chord’s root note is derived from the 1st, 4th and 5th notes of that key’s natural minor scale. The D natural minor scale notes are: D E F G A Bb C. )

Key: Chords m = minor.

Dm: Dm Gm A

Am: Am Dm E

Em: Em Am B

Bm: Bm Em F#

F#m: F#m Bm C#

The 1-6-7 is also a common progression:

Dm: Dm Bb C

Am: Am F G

Em: Em C D

Bm: Bm G A

Also the 2-5-1:

Dm: Em7b5 Am Dm

AM: Bm7b5 Em Am

Try the 1-4-7:

Dm: Dm Gm C

Am: Am Dm G

Try playing each of these progression types several times. Perhaps even choose one and write a song.- Bill Watson

Demo or Master?

Posted: June 11, 2013 Filed under: Song Demo Tip, Songwriting Tips | Tags: Demo or Master?, Demo to Limited Pressing Conversion Agreement 2 CommentsShould you have a demo made of your latest song or a master? That is should you use a service such as Play It Again Demos or should you use a studio such as Nashville Trax?

Do a demo if:

Do a master if:

Note that in 2012 AFM Local 257 here in Nashville approved the Demo to Limited Pressing Conversion Agreement which permits an upgrade from demo to master that gives credit for payments already made. Previously it was illegal to sell a demo.

Songwriting Tip : The Song Concept Is King

Posted: March 8, 2013 Filed under: Songwriting Tips | Tags: concept of song, inside song, michael o' conner, outside song, songwriting tip, unique song concept, unique song title Leave a comment My songwriting mentor, Michael O’Connor of Michael O’Conner Music, based in Studio City, CA constantly stressed the importance of a unique song concept. His company hits were mostly middle of the road and pop songs. (Note that there’s a Michael O’Conner based in Texas who publishes his own songs: not the same guy.) When I got into country music and moved to Nashville I quickly realized that what Michael applied to pop songwriting was even more true when writing country where the chord progressions are often simple and in many cases very little except the lyric separates one song from another. There are many techniques country songwriters employ but I think it’s safe to say, in country, developing a unique song concept is king of the hill.

My songwriting mentor, Michael O’Connor of Michael O’Conner Music, based in Studio City, CA constantly stressed the importance of a unique song concept. His company hits were mostly middle of the road and pop songs. (Note that there’s a Michael O’Conner based in Texas who publishes his own songs: not the same guy.) When I got into country music and moved to Nashville I quickly realized that what Michael applied to pop songwriting was even more true when writing country where the chord progressions are often simple and in many cases very little except the lyric separates one song from another. There are many techniques country songwriters employ but I think it’s safe to say, in country, developing a unique song concept is king of the hill.

A unique concept can be defined simply as the “idea of the song” or “what the song is about.” But the concept can also encompass the title. In fact, coming up with a great, unique title is the starting point for many hits.

When you want to write about a particular subject your first thought will likely be a cliché. Write down the cliché then try to outdo it with something that says that same thing in a way no one ever has before. Locked Out Of Heaven by Bruno Mars is a great example of a concept title that’s unique. A good country example is the Jamey Johnson penned In Color. The singer is looking through his Grandfather’s old black & white photos taken at highly emotional moments in his Grandfather’s life as his Grandfather discusses them. Grandad ends each chorus with, “You should have seen it in color.” Powerful. It’s the kind of hook line that resonates so deeply the first time you hear it, it takes your breath away.

Why do you want to mess with this title creating and lyric crafting stuff, why not just let the words pour out and let the chips fall where they may? Because publishers are your best pathway to getting a song cut and publishers know they have a much better chance of making that happen if a song has a unique concept/title than something bland and unimaginative. So their antennas are up for great titles. Impress them with a great one that’s developed into a complete, equally well developed lyric and a phone call to contract your song probably isn’t more than five minutes away. Anyone can write “My Grandad showed me some old pictures and wished I had been there to see it for myself.” Not everyone can boil it down to, “You should have seen it in color.”

The paradox for most songwriters is when they look at the pop or country charts and see clichés or common phrases used as titles and think,”That dude at Play It Again Demos telling me about the importance of great titles and concepts doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” Or they listen to the radio and think, “Hey my song is better, therefore it should be a hit.” If the unpublished songwriter’s song really is better it’s usually because the artist songs were written by the artist or someone with an inside track to them. It’s the artist’s fan base and clout that get the song on the charts and garner sales.

Yes, Hank Williams, Sr. wrote “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” and Dolly Parton wrote “I Will Always Love You” two songs that almost surely were outpourings of emotion that came out ready to cut as-is, no tweaking necessary. And both writers had enough experience to know that injecting craft and cleverness was the wrong way to go for those particular songs. But both had their share of songs that obviously were crafted to the max. And most songs by less experienced songwriters fall far short of that out-of-the-gate perfection.

Only compare your work to “outside” songs on the charts that were written by writers who have to run the same gamut of gatekeepers song publishers, producers, etc. you do. In most of those cases you’ll find a unique concept is the catalyst that propelled the outside song all the way to its current position on the charts- Bill Watson